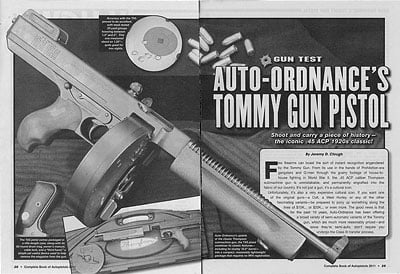

Shoot and carry a piece of history—the iconic .45 ACP 1920s classic!

The Complete Book of Autopistols 2011, page 28 ~ 33

By Jeremy D. Clough

The TA5 pistol comes packaged in a rifle-length case, along with its 50-round drum mag, owner’s manual, cable lock, and a “third hand,” a simple yet useful device used to help remove the magazine from the gun.

Few firearms can boast the sort of instant recognition engendered by the Tommy Gun. From its use in the hands of Prohibition-era gangsters and G-men through the grainy footage of house-to-house fighting in World War II, the .45 ACP caliber Thompson submachine gun is unmistakable, and permanently engrafted into the fabric of our country. it’s not just a gun, it’s a cultural icon.

Unfortunately, it’s also a very expensive cultural icon. If you want one of the original guns—a Colt, a West Hurley, or any of the other fascinating variants—be prepared to pony up something along the lines of $15K… or $20K… or even more. The good news is that for the past 10 years, Auto-Ordnance has been offering a broad variety of semi-automatic variants of the Tommy gun, which are much more reasonably priced—and since they’re semi-auto, don’t require you undergo the Class III transfer process.

Predictably, the line includes the 1927A1—the most distinctive of the Tommy Guns, with its finned barrel, Cutts compensator, and finger-grooved vertical foregrip—as well as the less flamboyant M1. As issued to the U.S. military, the M1 retained the drooping lines of the 1927’s buttstock as well as the same general receiver profile, only with a businesslike smooth barrel and straight forestock. Both are available with receivers made from either steel or lightweight aluminum, and with barrels in either 16.5-inch or the original 10-inch lengths, with the latter being subject to Class III registration as Short Barreled Rifles (SBR). All are chambered for .45 ACP and, depending on the model, are fed by a 30-round stick magazine, drums that hold anywhere from 10 to 100 rounds, or both.

Gun Details

Among the latest models they’ve introduced is the TA5 pistol, generally based on the 1927 model. Combining an alloy receiver with the short 10.5-inch barrel, it comes with a 50-round drum magazine and makes for a compact, fearsome package that’s surprisingly handy. Weighing in at a little over 5 pounds, the TA5 is just over 23 inches long, and balances well—perhaps because the rear of the receiver hangs well back behind the walnut pistol grip. For the serious aficionado, you can even get a violin-shaped hardcase for it.

The barrel is the classic finned version, although it comes without a Cutts compensator (you can order one from Auto-Ordnance), and the trademark vertical foregrip has been supplanted by the horizontal one found on the M1. While this may seem an odd omission, putting a vertical foregrip on a handgun subjects it to Class III registration—something the TA5 pistol is intended to avoid.

Sights consist of a prominent blade front and a flip-up rear that allows you to select either a shallow, rudimentary notch or an adjustable ring sight that’s calibrated (somewhat optimistically, perhaps) to what appears to be 600 yards. The ring is finely checkered to cut glare, and proved capable of excellent accuracy.

The controls are the classic ones: a top-mounted charging handle with a rounded, checkered surface and a slot machined through it so you can see the sights, as well as a 180-degree safety on the left side of the gun, easily reached by the thumb, and the waffle-stamped, angled magazine catch, which also falls readily to hand.

Loading Up

Ah, the magazine—that round, bestial thing that devours an entire box of .45 hardball before it’s ready to be slid into place and promptly emptied. For those who have never used a Thompson drum magazine—I hadn’t—the process is daunting at first, but quickly mastered. As I learned, loading it is half the fun: getting it in and out of the gun is the other half.

First, to load it you lay the magazine on its back, with the winding lever upwards. Press in on the spring steel clip that keeps the lever in place, and slide the winding lever off of its axle, which free the top cover so you can remove it. Now, you stack the rounds into the body of the now-open magazine, bullets pointing upwards, in rows of five. You’ll wind up with four double rows, and two single rows. Carefully put the top cover back in place, then snap the lever back on, making sure to orient it properly on its axle: if it’s not right, it won’t go on—and if the top cover isn’t all the way down, it won’t fit, either. With that done, rotate the lever until you’ve heard the recommended 9 to 11 clicks—and these are the loud clicks, not the softer ones, you’ll know it when you do it—and you’re ready to go. Since winding the magazine up is how it places the right amount of tension on the cartridges within, if you don’t do it enough, the rounds won’t feed. Also, and this is common sense… don’t take the magazine apart while it wound up.

While it all sounds terribly complicated, it’s really not. Just out of curiosity, I clocked the whole procedure, from taking the magazine apart to winding it once loaded, and it can be easily done in 90 seconds, a minute flat if you’re rushing.

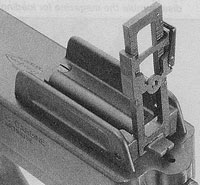

Now, time to get it in the gun. Because the bolt travels through the feeding trough cut through the top of the magazine, it must be withdrawn for the magazine to be slid into place. While it’s theoretically possible to manually hold the bolt back, depress the magazine release, and slide the magazine in from the side, that’s not the best way. First, pull the bolt all the way back, and move the little lever in the magazine track (on the forward part of the triggerguard) upwards to lock the bolt in place. Then, while depressing the magazine release, the magazine can be slid into place from either side. Draw the bolt back to release it from the catch, drop it, and you’re ready to go with a round chambered.

The fun part is what happens when the magazine is empty, since you still have to have the bolt in the rearward position to get the magazine out, but you can’t reach the tab to lock it in place. The field expedient method I used was to flip the gun upside-down, brace the cocking knob against the range table, and push the gun forward until the bolt was far enough back for the magazine to be removed. Had I read the instructions, however, I would have encountered a small device called the ”third hand,” that comes packaged with the gun.

Designed to be inserted up the magazine chute from the rear (the magazine release has to be depressed to do this) the third hand magically pushes up on that little tab that you can’t reach with the magazine in place, allowing you to lock the bolt back. Depress the magazine release again, remove the third hand, slide the magazine out to the slide—brilliantly simple.

Range Time

Now, on to shooting it. The first question is, how? While it’s possible to fire the TA5 like an ordinary pistol, you’ll get tired of that in short order — it’s simply too heavy. I had great fun shooting it much as I would a rifle: held up to eye level, right hand on the pistol grip, left on the forend, just without a buttstock. Accuracy was surprisingly good shooting like this. I could bounce cans and such around the range easily, and hit some targets out at the 100 yard berm. using the flip-up rear ring sight, things got much better: on paper, resting the gun and firing from the prone position, I was able to post consistent groups in the 1.5- to 2-inch range at 25 yards, with some smaller than that. The trigger pull didn’t hurt, either: while it didn’t have the sharp crispness we expect from, say, an M1911, it had a smooth, gentle roll to it, and wasn’t at all unpleasant to shoot.

But these small groups were all with the ring sight, and much of the other shooting I did was using the slot in the cocking knob to center up the prominent front sight. I suspect I am not the only one who had difficulty using the shallow v-notch; frankly, it was so small, I didn’t even notice it until I had a fair number of rounds through the gun. After all, I was doing well using the front sight and cocking knob, so why complicate things?

Since the TA5 is advertised as being only compatible with ball ammunition, in testing, I fired 500 rounds of 230-grain ball ammunition, which was provided by Black Hills Ammunition. I’ve gone through thousands of rounds of Black Hills ammunition in several calibers, and it’s excellent stuff; I’ve used their 230-grain jacketed hollowpoint as my standard carry load for a couple years now, and have great confidence in it.

Reliability was good, once I figured out how many times to crank the winding knob on the magazine (the first magazine, which I didn’t wind enough, didn’t run well, and that’s my fault). Afterwards, there were about a half-dozen or so malfunctions where the cartridge fed partially into the chamber, with the bolt almost closed be-hind it, but without the extractor snapped over the case rim. Drawing the bolt partially back and releasing it caused it to close properly, and the cartridge to fire and extract appropriately. There was no other type of malfunction. Oddly enough, though, the last magazine I fired out of the TA5 pistol had several more of these malfunctions, which leads me to assure it could be another magazine winding issue.

Final Notes

With the TA5 pistol version of their classic 1927, Auto-Ordnance has reintroduced another variant of their timeless subgun. Accurate, easy to handle and fun to shoot, it’s an excellent choice for those who enjoy the historical significance or the gun—or just its tough looks—but don’t want to go through the Class III licensing process to obtain a full-auto original or a short-barreled version of the currently produced rifle. Find out more by calling 508-795-3919 or tommygun.com.