.30 Carbine Combo

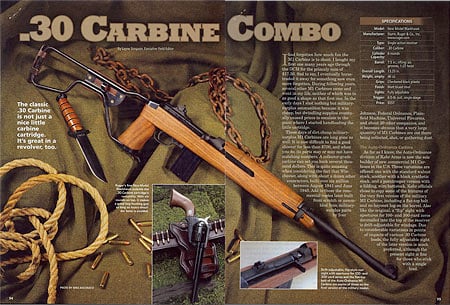

The classic .30 Carbine is not just a nice little carbine cartridge. It’s great in a revolver, too.

Shooting Times Magazine, February 2011, p. 54 – 58

By Layne Simpson, Photo by Mike Anschuetz

I had forgotten how much fun the M1 Carbine is to shoot. I bought my first one many years ago through the DCM for the princely sum of $17.50. Sad to say, I eventually horse-traded it away for something now even more forgotten. During following years, several other M1 Carbines came and went in my life, neither of which was in as good a shape as that first one. In the early days I shot nothing but military-surplus ammunition because it was cheap, but dwindling supplies eventually caused prices to escalate to the point where I started handloading the little cartridge.

Those days of dirt-cheap military-surplus M1 Carbines are long gone as well. It is now difficult to find a good shooter for less than $700, and when you do, its parts may or may not have matching numbers. A collector-grade carbine can set you back several thousand dollars. This is quite amazing when considering the fact that Winchester, along with about a dozen other contractors, built over six million between August 1941 and June 1945. Add to those the commercial copies later built from scratch or assembled from military-surplus parts by Iver Johnson, Federal Ordnance, Plainfield Machine, Universal Firearms, and about 20 other companies, and it becomes obvious that a very large quantity of M1 Carbines are out there being collected, shot, or gathering dust.

The Auto-Ordnance Carbine

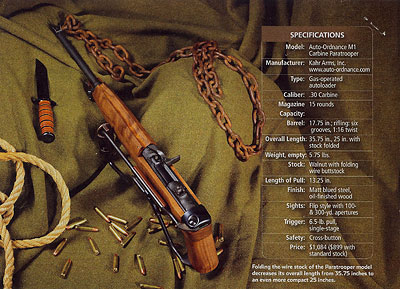

As far as I know, the Auto-Ordnance division of Kahr Arms is now the sole builder of new commercial M1 Carbines in the U.S. Three variations are offered: one with the standard walnut stock, another with a black synthetic stock, and a paratrooper version with a folding, wire buttstock. Kahr officials chose to copy some of the features of the very first version of the military M1 Carbine, including a flat-top bolt and no bayonet lug on the barrel. Also like the original, a “flip” sight with apertures for 100- and 300-yard zeros dovetailed into the top of the receiver is drift-adjustable for windage. Due to considerable variations in points of impacts of various .30 Carbine loads, the fully adjustable sight of the later version is much preferred, although the present sight is fine for those who stick with a single load.

During manufacture the front sight blade of a military M1 Carbine with the flip rear sight was intentionally made too tall and then filed down to the proper zero during function testing of the firearm. Since the Auto-Ordnance carbine shot quite low, I can only assume that the sight was left tall for the customer to modify. Due to variations in points of impact of not only various factory loads but of handloads as well, I consider this a great idea. If the rifle were mine, I would first determine which load is most accurate and then file its sight to zero with that load. This is a file-shoot-file-shoot procedure, and it is important to remove only a slight amount of metal between groups; once the metal is gone there is no putting it back. Taking a mere .006 inch off the sight will raise group point of impact about an inch at 100 yards.

A more practical option is to replace its rear sight with a fully adjustable sight, either military surplus or newly manufactured. Just such an aftermarket sight is available from Auto-Ordnance as well as Kensight Mfg., the latter sold through Brownells. Switching out the rear sight may also require a front sight blade of a different height.

With decent ammo most military M1 Carbines in good condition will average 3 to 5 inches for five shots at 100 yards. Nothing to brag about by today’s standards, but we must keep in mind that it was primarily intended to replace the 1911 pistol in the hands of military officers, tank commanders, and various support personnel, such as cooks, medics, and mechanics. In addition to being accurate enough for close- to medium-range shooting under combat conditions, it is far easier to shoot accurately than any pistol. This held especially true for the thousands of green recruits who had never handled any type of firearm before joining the Army.

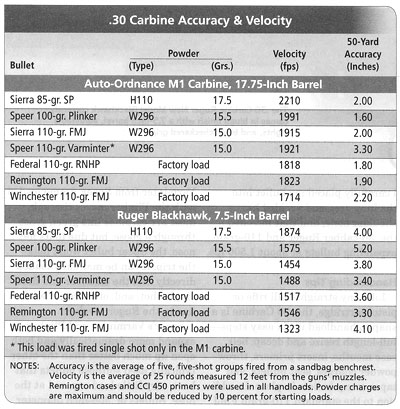

My original intent was to accuracy-test the Auto-Ordnance carbine at 100 yards and then move to the 50-yard range when shooting a Ruger Blackhawk revolver in .30 Carbine. Unfortunately, on the day I set aside to shoot the two, the longer range at my gun club was closed, so I had no choice but to wring out both at 50 yards. Even though my eyes are not as young as they once were, I am still quite capable of shooting 1-inch groups at that distance with military-grade aperture sights and about 2 inches with open sights.

Feed it good ammo in good magazines and keep it reasonably clean, and the M1 Carbine is about as reliable as any autoloader. When shooting the Auto-Ordnance carbine, I experienced one smokestack and two failures to fully chamber with factory ammo. After about 200 rounds, I gave its boltface, chamber, and bore a good brushing with cleaning solvent, and from that point on the little critter never missed a lick.

The Ruger Blackhawk

The .30 Carbine chambering has also been offered in a few handguns through the years. There was an autoloader from AMT called the Automag III and a single-shot Contender from T/C. Those are long gone, but the .30-caliber Ruger New Model Blackhawk has been hanging around since 1968. Recoil of the Ruger is about the same as for the .357 Magnum loaded with a 110-grain bullet, but muzzle blast and flash are greater. I used to hunt wild pigs a lot with hounds and most of the shooting was inside 15 yards. I used about every handgun you can think of, including a .44-caliber cap-and-ball revolver loaded with blackpowder. About anything worked as long as I carefully placed my bullet into the lung area and avoided heavy shoulder bone, and that included the .30-caliber Ruger and 110-grain expanding bullets at about 1,500 fps.

Handloading Tips

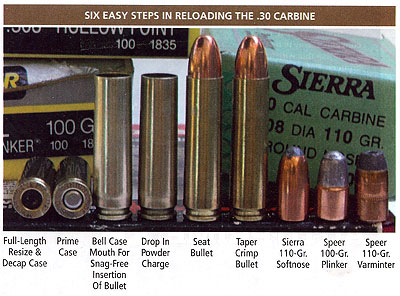

Like any straight-wall rifle or pistol cartridge, the .30 Carbine is a snap to handload in six easy steps–full-length resize and decap, bell case mouths, insert primers, throw powder charges, seat bullets, and taper crimp bullets in place. In addition to the standard 110-grain FMJ and softnose bullets from Sierra, Speer, and Hornady, we have the 100-grain Plinker and a 110-grain flatnose hollowpoint called the Varminter from Speer. Ammo loaded with the Plinker moves through most M1 carbines like green grass through a goose, but due to its flat nose, the Speer bullet won’t make the trip. It can be manually loaded directly into the chamber and fired single shot, and, of course, it works fine in the Ruger revolver.

Speer’s Varminter and Plinker expand more dramatically and both open up much better than the other typically used softnose bullets that have very little lead exposed at the nose. Bullets of .308-inch diameter designed for the .30 Mauser and 7.62x25mm Tokarev also work in the .30 Carbine, especially in the Ruger Blackhawk. They include the 86-grain softnose and 90-grain hollowpoint from Hornady and the Sierra 85-grain softnose. All expand quite nicely at revolver velocities, and from the carbine the Sierra is a real bomb.

Cases produced commercially in the U.S. can vary in length by as much as .006 inch, and since the .30 Carbine headspaces on its mouth, those variations can result in round-to-round variations in the amount of energy delivered to the primer by the firing pin. This can affect accuracy, and while the typical M1 carbine may not be inherently accurate enough for it to make a difference, trimming the entire batch to the same length prior to loading them doesn’t hurt anything. I checked three brands of once-fired cases, and they varied in length from a minimum of 1.284 inches to a maximum of 1.290 inches. Shortest among the Remington cases I used for this article was 1.286 inches, so I trimmed the entire batch to that length. Some reloading manuals list trim-to length as 1.280 inches, while others recommend 1.286 inches. I have never found it necessary to go below the latter length.

Both the M1 Carbine and its .30-caliber cartridge were designed by Winchester, and it was the first U.S. military cartridge to be loaded with spherical powder. The propellant later became available to the canister trade as Winchester 296 Ball Powder, or W296 for short. Sometime later Hodgdon started selling basically the same powder but called it H110. Even though the two are the same, different lots can have slightly different burn rates, so load data is not always interchangeable between the two. Both deliver top velocities with all bullet weights, but they leave a lot of residue in chambers and bores and on fired cases. Other powders, such as Herco, SR 4756, IMR-4227, H4227, and Lil’ Gun, burn more cleanly, but they seldom reach velocities as high with all bullet weights as W296 and H110. I long ago settled on the CCI 450 Magnum Small Rifle primer for igniting those two powders in the .30 Carbine.

Full-length resizing dies made for the .30 Carbine are designed to taper crimp the mouth of the case snugly against the bullet. In addition to removing the bell from the mouth of the case, it helps to prevent a bullet from being driven deeper into the case during the feeding cycle of the carbine. SAAMI maximum diameter at the mouth of a loaded round is 0.336 inch, but through the years I have found that the bolt may not fully lock into battery with a round that fat up front if the chamber of a particular carbine was reamed on the minimum side of the allowable tolerance range. This results in misfires, and the problem often worsens as propellant fouling from many rounds builds up in the chamber. Factory ammo from Winchester, Remington, and Federal ranges from 0.330 to 0.334 inch at the mouth. For handloads, I prefer to adjust the taper-crimp die to squeeze mouth diameter as close to 0.330 inch as the thickness of the brass will allow. This assures that the round will travel all the way home in a dirty chamber, yet the mouth is still large enough in diameter for positive headspacing of a chambered round.

So what’s the .30 Carbine good for? Well, for starters, it has bagged plenty of deer through the years, but that does not make it a deer cartridge by any stretch of the imagination. I’d say it is close to ideal for toppling a treed cougar from a tall cedar. I have never bagged a turkey with the little cartridge, but I see no reason why it should not work in Texas and other states where the big bird can be legally taken with rifles. It should be just as deadly on javelina, and I’m thinking it would be a fun way to surprise a called-in coyote standing with a shocked look on its face just off the toes of my boots. Other than that the only thing I can think of to say about our littlest .30-caliber rifle cartridge is it is as much fun to shoot in the M1 carbine today as it was a few decades back when you could buy one for $17.50.