At the NRA Museum, Tommy Gun Devotees Can Zero In on a Classic

Style, The Washington Post, March 22, 2004

By Stephen Hunter (Washington Post Staff Writer)

At 2:23 p.m. on Nov.1, 1950, news suddenly arrived at the Secret Service office in the East Wing of the White House that across the street, men were trying to “shoot their way into Blair House, where Harry Truman was taking a nap.

James Rowley, agent in charge of the White House detail, responded with four words, spoken, one imagines, rather forcefully: “WHERE’S MY TOMMY GUN?”

You have to admit: He had a point.

Fortunately, Rowley didn’t have to pull the trigger that day, and the agents at Blair handled their emergency with dispatch and heroism. But Rowley’s cry reflects almost a half-century’s worth of loyalty by American police and military men toward Brig. Gen. John Taliaferro Thompson’s baby when things got shaky and high quantities of firepower were necessary.

It also reflects a half-century’s worth of fascination in popular culture, where the Thompson submachine gun became an icon. Bogart carried one in “Sahara” and “High Sierra,” Edward G. Robinson took a lungful of T-gun product and it was, Mother of God, the end of Rico in “Little Caesar.” Dillingers, both in life and on film, let fly with the subgun’s rat-tat-tat. Then, when the guns became a military standard in World War II, they surfaced in just about every movie made about that conflict, most recently and most famously in the hands of Tom Hanks as he saved Private Ryan.

Photo by Gerald Martineau-The Washington post

The actual things themselves have long since vanished from police or military gun vaults, replaced in our fabulous modern age by lighter, faster, uglier, plasticized, teflonized, ventilated thingamajiggers, high on efficiency, low on romance. Most of the old tommies were junked or sold off to Third World militaries that have by now junked them. The few operating survivors escalated exponentially in value-especially after a 1986 federal law froze the number of automatic weapons in the country-and therefore disappeared into private collections, where high-end aficionados could admire them over a glass of fine port in front of the fireplace after a hard day clipping coupons.

So if you called out, “Where’s my tommy gun?,” the answer would be: “In your local millionaire’s mansion.” But today it’s different. Mr. and Mrs. America, your tommy gun is in the National Rifle Association’s National Firearms Museum just outside Washington, along with 59 of its buddies, in an unprecedented gathering of specimens of the American instrument that made the ‘20s roar, the ‘30s rock and the ‘40s roll.

In fact, it’s probably the largest gathering of Thompson submachine guns under one roof since the night of June 5, 1944, when U.S. paratroopers smoked and joked, then cocked and locked, in various British hangars before climbing into their transport planes and jumping into Normandy early the next morning.

The $2 million exhibition, which showcases the best and rarest of the guns in private ownership as organized by the Thompson Collectors Association, is in the museum’s William B. Ruger gallery , under the formal name “Thompson: On the Side of Law and Order,” which happens to be the motto of the gun’s manufacturer, the Auto-Ordnance Corp. A purist might argue a better title would be “Thompson: On the Side of Law and Order, Most of the Time,” for much of the gun’s famous deployment was rooted not in behavior but in misbehavior. Another kind of purist might wish that the gun’s serious mythologizing in popular culture had been more rigorously examined, even if the museum just did close its spectacular exhibit on movie guns, “Real Guns for Reel Heroes,” which examined this issue in detail.

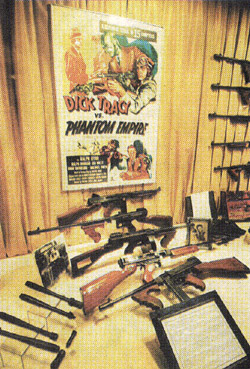

Still, if you have a fondness for these old American beauties-and who doesn’t, no matter their position on the dreaded gun issue-this is the place to go. It’s arranged, as one might expect, chronologically, taking the weapons from first models to standards to later World War II-issue simplifications and finally to the semiautomatic replicas on the market today. It exhibits not only the guns themselves, 60 of them, but also their accouterments, their memorabilia, their accessories, their cleaning implements, all the little gewgaws and gimcracks that make the typical detail-obsessed gun collector dizzy with pleasure. For anyone else with a casual interest in firearms as historical objects, as works of industrial design and as reflections of aesthetic sensibilities, the impact of so much hardware in such a little space will knock you almost as woozy.

And, of course, if you study American guns, you quickly run into a familiar figure: That would be a flinty entrepreneur who shrewdly applied a realpolitik analysis to the word, figured out an unsatisfied market niche and developed a product to fill it. That’s true of most industries, but particularly of the firearms industry, where guys named Colt and Winchester and Smith and Wesson and Marlin became small-scale industrial barons by understanding that a growing nation needed lots of good guns. It was certainly true of the aforementioned late benefactor Ruger, who manufactured guns for the common man to such a degree of success that he was able to endow handsomely the NRA’s museum with its impressive exhibition space.

And it’s certainly true of Thompson, West Point grad and firearms expert, who watched in horror as the World’s infantrymen were slaughtered like hogs on butcher day on the Western front in World War I. He saw the need for-and the market for-a light, powerful, battle-reliable weapon that would make fire-and-maneuver war fighting possible and spare his own nation’s soldiers the ignominy of the trenches. He set about to make it happen.

Thompson himself didn’t invent the gun (though he did invent the term “submachine gun”). He found a moneyed investor (Thomas Fortune Ryan) and thereby raised the capital to assemble a first-rate design team. But the two primary engineers-Oscar Payne, of the unschooled genius type that also figures prominently in firearms design, and Theodore Eickhoff, a gifted mechanical engineer-surpassed even their sponsor’s grandest hopes. They invented a classic.

The gun they came up with, in its final form, was reliable, accurate, light enough (it weighed about 10 pounds), relatively easy to manufacture, powerful. And it was one other thing, almost accidentally: It was beautiful.

As a consequence, the Thompson, like a few other guns, a few automobiles, a few paintings, a few symphonic bars, a few first paragraphs, became a phenomenon that transcended its design and utility. It was an example of what might be called charismatic harmony, a choreography of slopes and flats and slants and angles as executed in brilliantly machined steel and elegantly finished wood that compels simply by the nature of its grace. That, as much as anything, is why it lasted and why even when better, cheaper, lighter weapons became available, both the real-world operators and their cinematic coefficients preferred to stay with the Thompson.

The exhibit has some rarities: It has two of the company’s first, but false-start, products, .30-caliber semiautomatic rifles that were meant to replace the Army Springfield and predated the famous M-1 Garand rifle of World War II fame by two decades. But the boys found that their mechanism worked most efficiently with a .45-caliber pistol cartridge, to which they committed early on. Three of Auto-Ordnance’s prototypes or pre-Thompsons, including Serial No. 7, which was designed in 1919, are displayed. They demonstrate that even at the inception of the project, Thompson’s designers had come across that signature profile, the modern, rigorous angularity of the bolt housing (usually called a receiver) in counterpoint to the graceful thrust of the two wooden grips, the pistol grip under the trigger group and the foregrip, under the finned barrel. When put into production, a stock was added, which reiterated the line of those two sculptured handfuls of wood, which gives the whole thing a pleasing unity. It’s not parts: it’s a whole. It’s somehow rakish and ergonomic at the same time. Grab me, shoot me, the gun seems to yell.

The whole thing leaps to hand, and points beautifully. Held to the shoulder, its sights present themselves smartly. It’s heavy enough to absorb much of the bite of the recoil of the powerful cartridge.

A particularly nifty stylization is the drum, a circular magazine set in front of the trigger group, holding either 50 or 100 cartridges. The drum gives the gun a signature uniqueness so essential to classicism. Like a Coke bottle or Mickey’s ears, it’s an almost universally recognized symbol of a certain something American. Kilroy was here, it tells the world.

The guns Thompson first produced arrived in the marketplace too late to warrant the large-scale military contracts he had dreamed of, since the war to end all wars had ended itself. But, of course, it hadn’t ended wars: Smaller, elite units saw the genius in the guns. The Marines used them in Nicaragua, the Navy gunboaters in China, the gangsters in Chicago and the directors in Hollywood.

The funny thing is, Thompson didn’t get rich. In fact he nearly went broke, and by the time the company was taken over, in 1939, by another financier, it boasted “a large debt, few assets, no production facilities and very few Thompsons in stock,” according to notes by Tom Woods, president of the Thompson Collector’s Association, in the exhibition catalogue.

That may be true, but for many, the between-the-wars editions of Thompsons were by far the finer variants. In those days, American guns were built (as were most American industrial products) with almost fetishistic care and elegance. The tommy guns were no exception, particularly a run of them manufactured on contract by Colt in the early 1920s. They had a lustrous blue finish of highly polished metal (the Colt polishers were famous). These were the classic “gangster” Thompson guns, with all the pizazzy works. They had finely machined Lyman adjustable stocks, the double vertical grips raked at that 38-degree angle and the Cutts compensator at the muzzle, which gave them such a sinister look and figured in so many Warner Bros. street and nightclub dramas. The thing looked great in a movie star’s hands, particularly if he had a pug-beautiful New York toughie’s face, a Camel dangling from the corner of his mouth leaking a filigree of smoke, dead calm eyes and a fedora a-tilt on his carefully oiled hair. The movies had discovered the power of the cool Bad Man, and then the bad-but-finally-good guy who finds redemption in the last reel. The tommy was one of the stations of the cross on the way to this spiritual deliverance.

But that was on-screen. In reality, it was the war, not the brothers Warner, that saved the Thompson from extinction. Though not a new design, it was judged new enough by a Department of War desperate for exactly the usage Thompson had envisioned two decades earlier. Moreover, it was simpler to gin up production on an existing design than to start over. As the factories churned them out, they simplified to save on manufacturing costs. The elegant Cutts compensator was no longer required, nor was the adjustable sight. The guns were no longer elegantly blued but roughly coated with tough phosphate, so they were a dull gray. The expensive-to-machine fins were jettisoned. From 1941 to 1945, more than 1,750,000 were produced, and they saw action everywhere, particularly where high-contact units were used, such as Marine raiders and Army rangers and paratroopers. The Marines who hit the beaches of the Pacific inlands loved them especially. In fact, one of the most famous photos from World War II features the gun: A Marine polishes off a Japanese sniper with his, while nearby a Browning automatic rifleman continues the advance. That’s fire-and-maneuver at its purest.

But for years, on the collector’s market, these wartime expedients, dubbed the Thompson M-1 and M-1A, represented the low end of the game because they weren’t up to the standards and the fame of the prewar beauties. Then Steven Spielberg made “Saving Private Ryan,” and he turned the collecting pyramid upside down: Now the cruder war guns, used so heroically by Hanks, skyrocketed in value. Unless you win a lottery or sell a screenplay, you’re probably not going to get into that market. They start at about $12,000 and accelerate quickly to the high 20s. And that is if you can find one for sale.

So the guns are and will remain the province of the rich, with the time on their hands to go through the lengthy process by which legal acquisition of a Class III (that is, fully automatic) weapon is possible. For the rest of us, the temporarily assembled legion of tommies at the National Firearms Museum will have to suffice. I don’t know about you, but in my book there’s nothing more dazzling to the eye and the imagination than a room decorated in a style called “Early Thompson.” Is this a great country or what?

The National Firearms Museum is open seven days a week and is at the NRA’s headquarters, 11250 Waples Mill Rd., Fairfax, near Exit 57 of Interstate 66.